For most of the internet’s history, the difference between a service (e-mail) and service provider (Hotmail) has been fairly clear. If you don’t like Hotmail for some reason, you don’t have to opt-out of e-mail altogether. Instead, you can create a new account with a different service provider and send a mass message to all of your friends. Once you’re certain that everyone has your new address, it’s curtains for Hotmail.

The recent turn toward highly-integrated, centralized “platforms” like Facebook and YouTube has muddied this picture. There is no gateway nor common protocol for exchanging friend requests between Facebook and Google+ like there is between Hotmail and Gmail. If I post a video to Vimeo or blip.tv, it isn’t going to show up in a search on YouTube. In a break from tradition, these service providers and the services they provide are tightly interwoven and difficult to pull apart.

The turn away from transparency leaves researchers with some tricky new challenges. First, what is meant by the term “platform” exactly and how is it different from a service provider? Second, how do we study these spaces if we can’t parse out the provider from the service?

Last year, Tarleton Gillespie examined the strategic use of the term “platform” by YouTube to appeal simultaneously to multiple audiences with different needs and values. Users, advertisers, professional media producers, and government regulators each understand the term “platform” to mean something different: a populist forum, two-sided market, commercial channel, or impartial carrier. As long as “platform” retains this ambiguity, it affords YouTube and others an advantage in both the marketplace and regulatory arena. They can benefit financially from popular media practices like vidding while at the same time avoiding responsibility for protecting participatory cultures from spurious copyright claims.

Though these service providers have proven themselves unreliable stewards of popular discourse, their “platforms” are nevertheless powerful tools to enable, circulate, and augment participatory culture civics. To better understand this tension between popular use and commercial interest, we need to extract the service from the service provider, an analytical practice that Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey Bowker called “infrastructural inversion.” Rather than look only at the content of tweets, YouTube videos, and Facebook statuses, we need to find ways to access the tangle of technologies and institutions that undergird these phenomena.

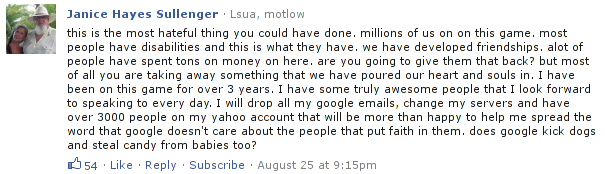

From the outside, the infrastructures of highly-integrated services like Twitter or Facebook are almost totally obscured. Users and researchers can only guess at the internal structures of these “black boxes” by poking at the box – either with a web browser or through the public API – and examining what comes out. (For a fine example, see Scott Smitelli’s systematic analysis of YouTube’s copyright filters from 2009.) But inductive exploration of black boxes is a slow, unreliable process with no guarantee that the infrastructure will remain stable from moment to moment. Time and again, service providers alter their infrastructure with little to no warning, causing headaches for the developers and users that rely on them.

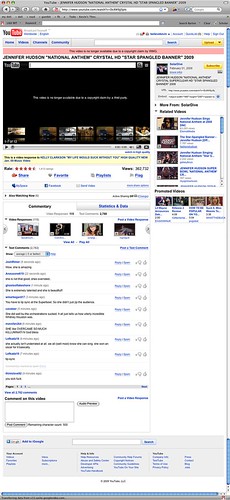

Another way to study infrastructure is by building it. Matt Ratto offers the term “critical making” to describe reflexive technology projects that engage both the symbolic and material aspects of media in society. Critical making asks us to imagine how existing infrastructures might be altered, improved, or replaced. For a small scale example, the image below is a mockup of what a YouTube page might look like if all of the metadata and user commentary were preserved after a video is removed for copyright violation. (Currently, this information is also removed when the video is taken down.)

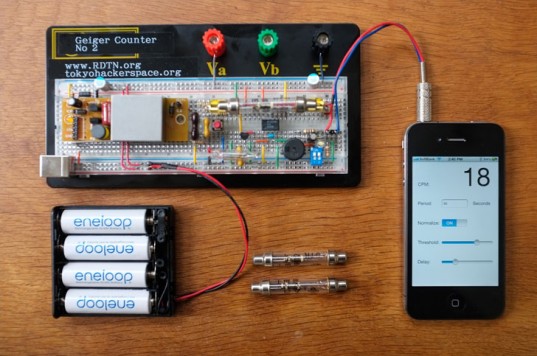

But critical making can occur at much larger scales as well. YouTube enables users to store, share, sort, comment on, respond to, and search for digital video. Numerous infrastructures might make this same set of verbs available. Miro Community uses free and open source software to build YouTube-like infrastructures for schools, local media, and other small civic organizations. Downloading their code and producing our own video infrastructure might yield a new perspective with which to examine YouTube itself. This approach is not about building an alternative to YouTube; it’s about focusing critical attention on infrastructure. What features would we want? What could we do with Miro Community that we can’t do with YouTube? What seems easy to implement and what seems difficult?

In 2010, a project called “Diaspora” raised $200,000 from 6,479 individual donors on Kickstarter to build a decentralized social network site with strong privacy controls. A year later, it has not attracted the volume of users that would make it the “Facebook-killer” some early supporters hoped it would be. But in a recent blog post titled, “We are making a difference” Diaspora’s founders point to features first publicly available in their 2010 alpha launch that are now implemented by Google+ and Facebook. Regardless of Diaspora’s future as a social network site, its mere existence contributed to shaping the infrastructures of more highly-capitalized, highly-visible social network sites.

Like Miro Community, Diaspora’s code is also freely available. Last winter, Sarah Mei changed the code so that users are asked to input their gender via an open text field rather than a drop-down menu (see above). This change means that users are not limited to a set of canned choices (“male” or “female”) but are free to identify however they wish. By building a feature of her ideal social network site in code, Mei crafted an experience for thousands of Diaspora users that calls into question the gendered assumptions embedded in most social network profiles.

Star wrote that infrastructure appears most readily when it breaks down. In our short study of the Living Room Rock Gods, for example, the importance of their messageboard infrastructure came to light only after their YouTube network was dismantled by copyright takedowns. Unfortunately, not every community will survive the devastating break downs that can happen when they depend on on private infrastructure. All of the organizations we’ve written about on this blog rely in one way or another on centralized “platforms” such as Vimeo, YouTube, Facebook, Tumblr, and Twitter. But how many are “disaster ready” should their preferred platform go down?

Critical making enables researchers to imagine and realize alternative infrastructures before disaster finds their fields of study. We cannot know what is happening inside of a “black box” like YouTube but building and playing with imitations, mockups, and experiments can provoke new ways of thinking and asking that draw attention to the crucial role of infrastructure in public discourse and civic engagement.