Reposted from Henry Jenkins’s blog (April 14, 2016).

This is the sixth and final entry in a series of posts showcasing the archive and resources we have assembled around our book project, By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism, which is being released by the New York University Press. This book was funded by the MacArthur Foundation’s Youth and Participatory Politics Network and written by Henry Jenkins, Sangita Shresthova, Liana Gamber-Thompson, Neta Kligler-Vilenchik, and Arely Zimmerman.

To Trump Trump’s Wall (and Hate)

by Emilia Yang

Donald Trump, real estate magnate and reality television star (against all odds and many people’s disbelief) is still running and leading in the primary elections of the Republican Party. During his campaign Trump has made various statements regarding illegal immigration using derogatory and generalizing terms to refer to the Latino population and even proposing to ban people from “Muslim countries” from entering the country. At the same time, various white supremacists and neo-Nazis organizations have shown support for Trump. Sadly, Trump’s hateful rhetoric not only has had a political effect on his fellow candidates’ positions about immigration, but it has also materialized through violence toward various racial groups, growing exponentially since I first started researching this topic in September 2015 [1].

Bloodied at St. Louis Trump rally. pic.twitter.com/3O65vsktvS

— Trymaine Lee (@trymainelee) March 11, 2016

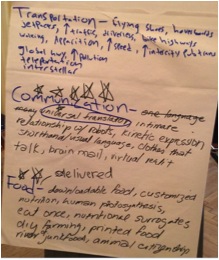

His proposal for “stopping” illegal immigration is to build a giant wall that would be called “The Great Wall Of Trump”[2]. It is evident that Trump and his supporters do not understand nor care about the humanitarian catastrophe that this would represent. Immigration and security experts warn that historically, US government border enforcement strategies have resulted in a massive increase in border crosser deaths [3]. As Gloria Anzaldúa writes in Borderlands, “The U.S.-Mexican border es una herida abierta [is an open wound] where the Third World grates against the First and bleeds” (1987).  Source: Ian Cleary, “The great wall of Trump”, August 26th, 2015 In a parallel context, students at USC and many other Universities across the Nation are struggling to call attention and overcome structural racism. Even though Trump’s hate speech does not directly link to the discrimination lived by the students on campus, it is disproportionately present in the media discourse that we are exposed to. The recognition of these issues provides a context for discussions about the realities of ethnic minorities such as the Latino community. In response, I created a media art project borrowing ideas from participatory co-creative media, agonistic design and installation and participatory art, which I called To Trump Trump’s Wall. The main objective of the project was to test different participatory frameworks (a workshop and an art installation) where a political issue is discussed, imagined, and represented in situ. A secondary objective was to find the difference in results between these two frameworks, and the third objective was to inspire fellow students, activists and academics to work with media making methodologies as communication alternatives that challenge both their perceptions of difference and their political engagement. The first iteration of this project was in the 2015 West Coast Organizing Conference hosted by the Student Coalition Against Labor Exploitation (SCALE) in what I will call the workshop framework. At this conference, student leaders from across the West Coast reunited to teach, support, learn from and inspire each other in their fights for justice. This inspirational weekend featured panels, caucuses, and workshops including To Trump’s Trump wall workshop, as discussion spaces for transgender, women, queer, people of color, working class, and people with disabilities. The second iteration of this project was presented in in the lobby of the SCI Interactive Media Building in the School of Cinematic Arts at the “Against Method” Exhibition that presented five ongoing PhD. student projects in what I will call the installation framework. During the organizing conference I was given a time frame of one hour to enable a discussion about undocumented issues with 20 participants. I was inspired by Think Critically – Act Creatively: Harnessing The Power Of Fiction For Social Good workshop [4] created by my colleagues Gabriel Peters-Lazaro and Sangita Shresthova, along with Karl Bauman, Ilse Escobar and Susu Attar in collaboration with community partners, artists, and activists and presented in the website By Any Media Necessary. This website provides resources that enhance and illustrate the forthcoming book By Any Media Necessary: Mapping Youth and Participatory Politics authored by Henry Jenkins and the Media, Activism & Participatory Politics (MAPP) group. In this world building workshop model, facilitators use prompt cards and ask participants to produce a one-word response to their prompt. Then they ask participants to imagine a future world set in a specific year (i.e. 2044) where fantastical things are possible and to come up with a narrative of what happens in this world, relating it to one of the themes fleshed out in the brainstorm. At the end, participants have to come up with a way to perform the story back to the whole group. Similarly, in Trump Trump’s wall workshop, I asked participants to discuss issues of immigration prompted with cards, reflecting on the immigrant experience, and then craft a message that they would like to inscribe in Trump’s wall if it was built and they had it up front. These are some examples of the cards given to the participants:

Source: Ian Cleary, “The great wall of Trump”, August 26th, 2015 In a parallel context, students at USC and many other Universities across the Nation are struggling to call attention and overcome structural racism. Even though Trump’s hate speech does not directly link to the discrimination lived by the students on campus, it is disproportionately present in the media discourse that we are exposed to. The recognition of these issues provides a context for discussions about the realities of ethnic minorities such as the Latino community. In response, I created a media art project borrowing ideas from participatory co-creative media, agonistic design and installation and participatory art, which I called To Trump Trump’s Wall. The main objective of the project was to test different participatory frameworks (a workshop and an art installation) where a political issue is discussed, imagined, and represented in situ. A secondary objective was to find the difference in results between these two frameworks, and the third objective was to inspire fellow students, activists and academics to work with media making methodologies as communication alternatives that challenge both their perceptions of difference and their political engagement. The first iteration of this project was in the 2015 West Coast Organizing Conference hosted by the Student Coalition Against Labor Exploitation (SCALE) in what I will call the workshop framework. At this conference, student leaders from across the West Coast reunited to teach, support, learn from and inspire each other in their fights for justice. This inspirational weekend featured panels, caucuses, and workshops including To Trump’s Trump wall workshop, as discussion spaces for transgender, women, queer, people of color, working class, and people with disabilities. The second iteration of this project was presented in in the lobby of the SCI Interactive Media Building in the School of Cinematic Arts at the “Against Method” Exhibition that presented five ongoing PhD. student projects in what I will call the installation framework. During the organizing conference I was given a time frame of one hour to enable a discussion about undocumented issues with 20 participants. I was inspired by Think Critically – Act Creatively: Harnessing The Power Of Fiction For Social Good workshop [4] created by my colleagues Gabriel Peters-Lazaro and Sangita Shresthova, along with Karl Bauman, Ilse Escobar and Susu Attar in collaboration with community partners, artists, and activists and presented in the website By Any Media Necessary. This website provides resources that enhance and illustrate the forthcoming book By Any Media Necessary: Mapping Youth and Participatory Politics authored by Henry Jenkins and the Media, Activism & Participatory Politics (MAPP) group. In this world building workshop model, facilitators use prompt cards and ask participants to produce a one-word response to their prompt. Then they ask participants to imagine a future world set in a specific year (i.e. 2044) where fantastical things are possible and to come up with a narrative of what happens in this world, relating it to one of the themes fleshed out in the brainstorm. At the end, participants have to come up with a way to perform the story back to the whole group. Similarly, in Trump Trump’s wall workshop, I asked participants to discuss issues of immigration prompted with cards, reflecting on the immigrant experience, and then craft a message that they would like to inscribe in Trump’s wall if it was built and they had it up front. These are some examples of the cards given to the participants:

The participants of the workshop engaged in very interesting discussions in groups. Their message was first drafted, both in words and visually on a storyboard, and then created and projected in the form of stop-motions animations. This mechanic enabled participants to learn how to animate figures and understand the logic of stop-motion animations while doing them.

The participants of the workshop engaged in very interesting discussions in groups. Their message was first drafted, both in words and visually on a storyboard, and then created and projected in the form of stop-motions animations. This mechanic enabled participants to learn how to animate figures and understand the logic of stop-motion animations while doing them.  The installation piece enabled an interactive experience of facing the wall, listening to a soundscape of the US/Mexico border. As in the workshop, participants where asked to create a character with a message that would face the wall with the materials and objects available.

The installation piece enabled an interactive experience of facing the wall, listening to a soundscape of the US/Mexico border. As in the workshop, participants where asked to create a character with a message that would face the wall with the materials and objects available.  The results are a large amount of media creations that will have a longer life than both frameworks. The animations created by the participants were politically charged, thoughtful, with calls for action. Participants stated that this was an innovative way of discussing any subject and they were interested in doing similar activities in their organizations and sharing their creations online. Despite being different frameworks of engagement, both enabled multiple discussions with diverse voices of students and faculty. These conversations generated media creations that address a relevant political theme with a playful approach. Overall, I believe that the collaborative and public creation of media activates new spaces for political debate and possibilities of expression within the participants, tapping into practices associated with participatory culture. My proposal for critical participatory making is to recognize us in others and harness the power of imagination to think otherwise. I propose participation as the place where real, inclusive and contested communication can take place, without erasing difference. I hope for participants not only to empathize with a real situation like the immigrant experience, but also to imagine an alternative positioning where they feel that they can confront this reality creatively. In this sense, I align with Henry Jenkins’ call to stimulate the civic imagination. For him, change emerges from the possibility of imagining a different world, infusing this imagination with a sense that change is possible, and understanding ourselves as agents capable of helping to drive that change. Thus the duality between “this is our reality” and “how we would like it” are displayed not as two isolated and abstract events, but as a contested open space in the present that we can transform through the encounter between reality and desire. In the case of Trump’s hate, racial discrimination and active calls for the enactment of violence, I believe we are entering into a completely different reality than the one I foresaw when developing the project, and we have to address this with multiple practices of civic imagination. The animal we are facing has mutated drastically. Lives are at risk and we have an ethical and moral responsibility to Trump Trump’s wall and hate by any media necessary. Citations: [1] Gabe Ortiz, “TIMELINE: Trump’s Racial Demagoguery Is Having Dangerous, Real-Life Consequences”, America’s Voice, September 16, 2015, http://americasvoice.org/blog/a-timeline-trumps-racial-demagoguery-is-having-dangerous-real-life-consquences/ Dara Lind, “What the hell is going on with violence at Trump rallies, explained”, March 14, 2016. http://www.vox.com/2016/3/14/11219256/trump-violent [2] “Trump on border: We’ll call it the great wall of Trump”, August 20, 2015, Real Clear Politics, http://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2015/08/20/trump_on_border_well_call_it_the_great_wall_of_trump.html [3] Clare Floran, “Trump’s Immigration Wall May Have Lethal Consequences”, August 25, 205, National Journal, http://www.govexec.com/management/2015/08/trumps-immigration-wall-may-have-lethal-consequences/119371/ [4] Workshops: “Think Critically – Act Creatively: Harnessing The Power Of Fiction For Social Good workshop” http://byanymedia.org/works/mapp/activity-1?path=activities References Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands: la frontera. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Luke Book Company Emilia Yang is an activist, artist, and militant researcher. Yang is currently a Ph.D. student in Media Arts + Practice in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. Her work has been interconnected with digital communications, performance, and public art. Her research focuses on participatory culture and its relationship to media, arts, and design. She is interested in transmedia storytelling framed through the question of how it can foster social change and civic engagement. Her art practice utilizes site-specific interactive installations, interactive documentaries, performance, and urban interventions, all of which explore social justice issues in participatory ways. Emilia completed an M.A in Communications at Penn State University. Her Master’s project researched the first social media protest to make it to the streets in her home country Nicaragua. She developed a participatory transmedia storytelling hub in a site called ocupainss.org with the objective to present the maximum number of stories and violations of human rights around this protest.

The results are a large amount of media creations that will have a longer life than both frameworks. The animations created by the participants were politically charged, thoughtful, with calls for action. Participants stated that this was an innovative way of discussing any subject and they were interested in doing similar activities in their organizations and sharing their creations online. Despite being different frameworks of engagement, both enabled multiple discussions with diverse voices of students and faculty. These conversations generated media creations that address a relevant political theme with a playful approach. Overall, I believe that the collaborative and public creation of media activates new spaces for political debate and possibilities of expression within the participants, tapping into practices associated with participatory culture. My proposal for critical participatory making is to recognize us in others and harness the power of imagination to think otherwise. I propose participation as the place where real, inclusive and contested communication can take place, without erasing difference. I hope for participants not only to empathize with a real situation like the immigrant experience, but also to imagine an alternative positioning where they feel that they can confront this reality creatively. In this sense, I align with Henry Jenkins’ call to stimulate the civic imagination. For him, change emerges from the possibility of imagining a different world, infusing this imagination with a sense that change is possible, and understanding ourselves as agents capable of helping to drive that change. Thus the duality between “this is our reality” and “how we would like it” are displayed not as two isolated and abstract events, but as a contested open space in the present that we can transform through the encounter between reality and desire. In the case of Trump’s hate, racial discrimination and active calls for the enactment of violence, I believe we are entering into a completely different reality than the one I foresaw when developing the project, and we have to address this with multiple practices of civic imagination. The animal we are facing has mutated drastically. Lives are at risk and we have an ethical and moral responsibility to Trump Trump’s wall and hate by any media necessary. Citations: [1] Gabe Ortiz, “TIMELINE: Trump’s Racial Demagoguery Is Having Dangerous, Real-Life Consequences”, America’s Voice, September 16, 2015, http://americasvoice.org/blog/a-timeline-trumps-racial-demagoguery-is-having-dangerous-real-life-consquences/ Dara Lind, “What the hell is going on with violence at Trump rallies, explained”, March 14, 2016. http://www.vox.com/2016/3/14/11219256/trump-violent [2] “Trump on border: We’ll call it the great wall of Trump”, August 20, 2015, Real Clear Politics, http://www.realclearpolitics.com/video/2015/08/20/trump_on_border_well_call_it_the_great_wall_of_trump.html [3] Clare Floran, “Trump’s Immigration Wall May Have Lethal Consequences”, August 25, 205, National Journal, http://www.govexec.com/management/2015/08/trumps-immigration-wall-may-have-lethal-consequences/119371/ [4] Workshops: “Think Critically – Act Creatively: Harnessing The Power Of Fiction For Social Good workshop” http://byanymedia.org/works/mapp/activity-1?path=activities References Anzaldúa, G. (1987). Borderlands: la frontera. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Luke Book Company Emilia Yang is an activist, artist, and militant researcher. Yang is currently a Ph.D. student in Media Arts + Practice in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. Her work has been interconnected with digital communications, performance, and public art. Her research focuses on participatory culture and its relationship to media, arts, and design. She is interested in transmedia storytelling framed through the question of how it can foster social change and civic engagement. Her art practice utilizes site-specific interactive installations, interactive documentaries, performance, and urban interventions, all of which explore social justice issues in participatory ways. Emilia completed an M.A in Communications at Penn State University. Her Master’s project researched the first social media protest to make it to the streets in her home country Nicaragua. She developed a participatory transmedia storytelling hub in a site called ocupainss.org with the objective to present the maximum number of stories and violations of human rights around this protest.