I tentatively offer here in the space of this blog some of the definitions that Lana and I have been working on. Since the blog has so far served as a platform for emerging (and not necessarily fully formed) ideas, it seems an appropriate place to share our work. But I would like to further emphasize that this list represents only a first attempt toward definition, and that we look forward to much revision and sustained conversation on this subject. (and maybe one day we will remove this post from the blog so that it doesn’t live forever as a first edition….?)

Methodologies for the Civically Engaged (shared reading)

What innovative methods can fans and/or the civic-minded employ in order to engage in civics, politics, activism, charity, or active community?

Here, I want to share the following papers that directly address or allude to methodology: Photo Voice, Alternative Media (Small-format videos), and Global Microstructures. Thanks to my colleagues Nan Zhao and Lana Swartz for bringing my attention to Photo Voice and Global Microstructures respectively.

Photo Voice and Small-format videos can potentially enable civic-minded groups to innovatively document their observations, express their feelings and voice their concerns with regard to the communities or peoples they want to bring attention to. E.g., with Invisible Children, wouldn’t it be interesting if the organization facilitated bottom-up production of videos and photo collages, in addition to attracting membership via its own cool, top-down ‘branding’ videos? Members of IC would become documentary photographers and filmmakers, and as IC looks beyond Uganda for its raison d’etre, its members would be armed with new methods to showcase the plight of newer afflicted peoples, or more wondrous still, let those peoples document themselves.

Global microstructures are difficult to implement as a methodology, since as the authors observe, these microstructures are emergent and “temporally complex”. However, it is not inconceivable that civic participation could / does occur in this format. If so, it is important for researchers to be on the look out for, and for orchestrators to understand in order to execute . After all, terrorist cells a la Al Qaeda, this article discusses, allegedly operate as global microstructures.

Links to articles:

Wang, C. & Burris, M. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology and use for participatory needs assessment. Health, Education & Behavior, Vol 24 (3): 369-387. http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/67790/2/10.1177_109019819702400309.pdf

Caldwell, J. T. (2003). Alternative media in suburban plantation culture. Media, Culture & Society, Vol 25: 647-667. http://mcs.sagepub.com/content/25/5/647.full.pdf+html

Cetina, K. (2005). Complex global microstructures: the new terrorist societies. Theory, Culture and Society, 5, 213-234. http://kops.ub.uni-konstanz.de/volltexte/2009/8098/pdf/Complex_Global_Microstructures.pdf

sharing readings (reflection)

This post is part of our research group’s regular effort to share readings.

Before offering an actual reading, I wanted to reflect briefly on how we might coordinate group readings. For our group, this is still a bit premature, since our initial mode is deliberately open and exploratory. But it’s easy to anticipate a day when we might want to push hard for cohesion, both conceptually and operationally in terms of specific bodies of literature to alternately support and oppose. Of course, our constituent researchers already have too much to read — and always have too much to read. So perhaps it would help to classify our suggestions.

Here’s one way to differentiate suggested readings: (a) core articles that define central concepts, as well as histories to differentiate our research from others; (b) branch leads that clarify our distinct research branches within our group; (c) provocation articles that raise new ideas, introduce uncertainty, or push for a change; and (d) FYI, for articles that are worth skimming the title and author, but otherwise are not required just yet. This still leaves open the decision of whether it is most appropriate to send the entire article, a marked-up version, an excerpt, or a summary/reflection — and whether we’re comfortable sharing our priorities on this blog (grin).

I do know several constituencies that might appreciate some kind of classification scheme: newcomers, partners and outsiders. Partners and researchers join the group annually (if not more often), and catching up to a shifting collective knowledge base is notoriously difficult. And of course, it might just help the rest of us too.

[Read more…]

Charity vs Activism

Lana and I have been thinking about the distinction between charity and activism (a very similar project to Neta’s on “civic engagement”). Here’s a preliminary list of texts we’re thinking of drawing on:

- Eliasoph, Nina. (1998) Avoiding Politics: How Americans Produce Apathy in Everyday Life.

- Blackstone, Amy. (2004) “It’s Just about Being Fair: Activism and the Politics of Volunteering in the Breast Cancer Movement. Gender and Society 18(3) pp. 350-368

- Burgess, J. Harrison, C. M. Filius, P. (1998) Environmental communication and the cultural politics of environmental citizenship.

- Burgess, Jean and Foth, Marcus and Klaebe, Helen (2006) Everyday Creativity as Civic Engagement: A Cultural Citizenship View of New Media. In Proceedings Communications Policy & Research Forum, Sydney

- Kennelly, Jacqueline Joan. Citizen youth : culture, activism, and agency in an era of globalization. Dissertation – http://circle.ubc.ca/handle/2429/769

- Jeff Goodwin, James M. Jasper, Francesca Polletta. Passionate politics: emotions and social movements. Chapter: “The Felt Politics of Charity: Serving the Ambassadors of God and saving the sinking Classes”

- Norris, Pippa. (2002) Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism

- Isin, Engin Fahri. Being Political: Genealogies of Citizenship

- Charity, Philanthropy, and Civility in American History edited by Lawrence Freedman, Mark McGarvie Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003

- Bremmer, Robert. Giving: Charity and Philanthropy in History. By Robert H. Bremner.

- McCarthy, Kathleen D. (1990) Lady Bountiful Revisited: Women, Philanthropy, and Power.

- Bickford and Reynolds (2002) “Activism and Service-Learning: Reframing Volunteerism as Acts of Dissent” Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition and Culture 2(2)

It’s a difficult set of terms to parse, given that new terms keep popping up (“being political,” volunteerism, advocacy, etc.) but we’re hoping to start pinning down some key concepts that will be useful as we continue our work. We’ll keep you up to date.

Shared readings

The readings I’d like to share are some that I have used for writing my blog post on “Civic engagement – defined and redefined”, and some others I wanted to use but didn’t get to…

Readings from political science and education relevant to thinking about new forms of civic engagement:

Dalton, R.J. (2008). The good citizen: How a younger generation is reshaping American politics. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Shea, D.M., & Green, J.C. (2007). The turned-off generation: Fact and fiction. In D.M. Shea and J.C. Green (Eds.), Fountain of youth: Strategies and tactics for mobilizing America’s young voters (pp. 1-18). Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Colby, A. (2008). The place of political learning in college. Association of American colleges and universities, Spring / summer, 4-12.

Owen, D. (2008, September). Political socialization in the twenty-first century: Recommendations for researchers. Paper presented at the Future of Civic Education in the 21st Century conference, Montpelier, VT. Electronic copy retrieved from http://www.civiced.org/pdfs/GermanAmericanConf2009/DianaOwen_2009.pdf

On the “scissor effect” : the claim that volunteering comes in place of political participation: Longo, N. (2004). The new student politics: Listening to the political voice of students. The Journal of Public Affairs 7(1), 1-14.

Data about young people’s volunteering and political engagement:

Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA (2009). The American Freshman: National norms for 2008. Los Angeles, CA. Available: http://www.heri.ucla.edu/publications-brp.php

Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, see http://www.civicyouth.org/

The MacArthur Series on Civic Engagement – a key source for many of the issues we’re discussing, with a foreword by Henry Jenkins, Mimi Ito and others.

Interfaces — e.g., Introducing Youth to DIY Punk Activism

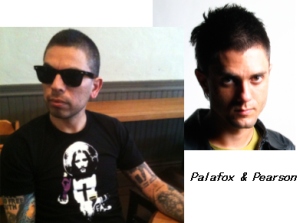

Earlier this week, I checked out an unusual intersection: two punk-hardcore activists were lecturing to 75+ teenagers at a Los Angeles university. But this wasn’t music camp. Rather, this was the last day of a college prep summer program,  hosted at USC for low-income and first-generation youth. Amazingly, the message stayed clear of “stay in school,” and focused instead on do-it-yourself (DIY) passion and activism. There are implications for our research group.

hosted at USC for low-income and first-generation youth. Amazingly, the message stayed clear of “stay in school,” and focused instead on do-it-yourself (DIY) passion and activism. There are implications for our research group.

Perhaps most importantly, the occasion underscored the “intersection dilemma”: how do learning institutions interface with civic sub-cultures (from punk activists, to the Harry Potter Alliance and Invisible Children)? For me, this intersection is a goldmine – a space of real drama, where subcultures put on a public face, and where institutions give uncertain attention to these emerging civic modes.

Of course, the actual people matter enormously. Justin Pearson and Jose Palafox (see above) are not your typical punk figures. While Pearson never graduated college, he and Palafox have been key players in DIY hardcore-punk since the mid 90s. They have been in countless bands – see, for example, this Swing Kids video with Pearson singing, and with Palafox on drums.

The activism of Pearson and Palafox is DIY, set against the punk subculture. As friends and independently, their bands have supported organizations ranging from Planned Parenthood, to PETA and the Black Panther Party. Palafox has made documentaries of the U.S.-Mexico border. Pearson just released his autobiography, and was on Jerry Springer with a hoax involving bisexuality.

Very briefly, I want to examine Pearson and Palafox as a kind of baseline for our research. Their example is valuable for its simplicity: compared to our current case studies, they do not have a fantasy content world (e.g., as compared to the Harry Potter fans); and second, the pair presented as individuals — without an organizational apparatus (such as the Harry Potter Alliance).

Civic engagment – defined and redefined

Civic engagement – defined and redefined

Neta Kligler Vilenchik

As our research team is interested in the ways in which groups that gather around shared interest and participatory culture may ‘evolve’ into civic and political engagement, the question of how to define these spheres of engagement has been raised several times.

Questions of terminology are of particular importance to our work, on several levels. First, we strive to understand how members of the organizations we are interested in define their own participation. Do they see it as charity? volunteering? civic engagement? political action? Second, and while taking into account the definitions used by interviewees, we need to establish the terms through which we as researchers discuss and interpret these activities. The terms and definitions we use must, in turn, be established in relationship and through conversation with other terms and definitions used in academia, whether in communication or in other, related disciplines. Finally, the ways in which we define these groups’ forms of engagement also have wider implications to the point we wish to make with our research. While being observers, we also have our own stake, in striving for wider forms of civic and political participation of young people to be acknowledged, accepted and valued.

In this blog post, I would like to survey some work that was been done in the political science literature, which calls for accepting wider forms of civic participation of young people. The field of political science is often considered, within and outside of that discipline, as the ‘authority’ for questions of forms of political action[1]. Surveying this work serves to show the contribution of our own work, which calls for a dual widening of the sphere of the political: both in terms of the types of action that is acknowledged, and in regards to the diversified styles of action that is valued.

A good starting point for this discussion is what Shea and Green (2007, p. 5) call “the myth of self-centered, apathetic younger Americans”. This refers to the view, common both in lay discussion and in many parts of academia, that young people in America are lazy, selfish, self-absorbed, and apathetic to civic matters. This myth, as Shea and Green quickly show, is very much mistaken. They cite studies showing that volunteering rates are higher among young people than among older adults, and higher among young people today than they were among the same age-group 20 years ago (see Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement). In contrast to what many think, young people volunteer not only due to service requirements in high schools and in order to be admitted to college, but—according to the amount of time donated—much beyond that. This tendency can furthermore be seen not only in college candidates, but throughout different ethnic groups and socioeconomic classes. Shea and Green conclude (2007, p. 5): “young Americans are anything but apathetic and immoral”.

Why then the gap between reality and common perceptions? Here comes the main point Shea and Green (2007) are trying to make. Along with a group of academics (e.g. Longo, 2004; Colby, 2008), they are worried that while young people increase their civic engagement, this does not extend, and even comes instead of, political involvement: “While youngsters seem more than willing to lend a hand cleaning up streams, helping others learn to read, and volunteering at the community soup kitchen, they shun politics—the very process that could produce solutions to polluted streams, poverty and adult illiteracy” (p. 8). Longo (2004) calls this the “scissor effect”—the claim that while young people volunteer much more (Longo, p. 63, calls this “service politics”), but participate much less in actual politics. The alleged reason for this is that young Americans feel marginalized with the political process, and so prefer to volunteer in specific projects, which enables them to feel immediate, concrete paybacks of their involvement. This is seen as creating “nothing less than a crisis of our democracy” (Longo, 2004, p. 61).

In fact, this view may be outdated, as recent findings show that political conversation among college freshmen in 2008 was at its highest in the last 40 years, and keeping up-to-date with politics was increasing (Higher Education Research Institute, 2009). But even if this were not the case, the problem with this point is the clear distinction it creates between political participation and civic engagement/volunteering. Political participation is implicitly defined here as engagement that happens within party politics, whereas volunteering—while appreciated—is deemed as politically insignificant[2]. But does this distinction hold water?

Consider the case of Mara. Mara, 22, was interviewed as a member of the LA chapter of the Harry Potter Alliance. Mara defines herself as politically active in a wide range of issues she sees as important, such as libertarian groups, gay rights groups, Jewish groups. Mara spends between an hour and two hours daily (!) as an ‘online activist’. She subscribes to the mailing lists of dozens of political groups, both ones she agrees with, and one she doesn’t, receiving and reading around 25 political emails a day. She researches about these groups, and uses her connection to groups she disagrees with in order to resist their efforts and send her own messages. For example, if an anti-gay-rights group calls members to protest companies that seem to support gay rights, she sends those same companies emails with the opposite message, calling them not to cave to the pressure of such groups. Several times a month, Mara attends events of the different groups she belongs to, and has been part of beach clean-ups, book donations, commemoration of soldiers and war victims, and other activities. But Mara is not registered for a political party, and sees the Democrats as being no better than the Republicans. According to traditional definitions, which see political action as occurring within the frames of party politics, Mara may be seen as another “disengaged young American”.

This aspect of participation, however, is not completely lost within the political science literature. One example is Russell Dalton’s book The Good Citizen (2008). Refuting the argument of declining political participation among young people, Dalton calls to accept new forms of political activism. According to this argument, what is changing are the norms of citizenship: duty-based norms of citizenship, the ones stimulating political voting, are declining. However, “engaged citizens apparently are not so drawn to elections, but prefer more direct forms of political action, such as working with public interest groups, boycotts, or contentious actions” (Dalton, 2008, p. 55). Dalton claims that the repertoire of political action is expanding, including not only voting, but also actions such as contacting officials directly, protesting, or engaging in communal activity: working with others to address political issues (p. 62).

This aspect is increasing within the realm of the Internet. As Dalton (p. 66) argues, “the Internet is creating a form of political activism that did not previously exist. The Internet provides a new way for people to connect to others, to gather and share information, and to attempt to influence the political process… The potential of the Internet is illustrated on the Facebook.com Web site, where young adults communicate and can link themselves to affinity groups that reflect their values as a way to meet other like-minded individuals”. Part of the reasons for young people’s new forms of engagement, in his view, has to do with “the growth of self-expressive values encouraging participation in activities that are citizen initiated, less constrained, directly linked to government, and more policy oriented” (p.68). Thus, “The engaged citizen is more likely to participate in boycotts, “buycotts”, demonstrations, and other forms of contentious action”.

Dalton finally names two examples of these new forms of engagement (p. 76), the example of Alex, an 18 year old from California who switched shampoos over animal testing, does not buy clothes produced by child labor, and helped organize a protest over the genocide in Sudan in her high school, before she was even eligible to vote. Jaime, a high school student in Maryland, created a teen group to encourage high school students to become socially involved, which boomed through Facebook. Dalton claims: “These two examples are not representative of all young people, but they illustrate the new focuses and forms of political activism that exist beyond elections, and that can enrich our democratic process if we understand these new forms of political action” (p. 76).

Dalton’s position, then, is much closer to the one our research team takes, than that of Shea and Green (2007), Longo (2004), or Colby (2008), in that it accepts and acknowledges new forms of engagement as politically significant. In the political science literature, Dalton’s expanded definition of what is seen as ‘engaged citizenship’ is seen as a “provocative thesis” (see David Magleby’s review of the book).

The work we do in our research team, however, goes a step or two further. We focus on these non-traditional forms of engagement, that do not consist only of voting, but include “boycotts, “buycotts”, demonstrations, and other forms of contentious action” (Dalton, 2008, p. 68). While some of this political action takes place in physical locations, much of it happens online, and this online action plays a big role in our research (whereas Dalton acknowledged it, but did not study it). Going further, the groups we examine show new ways of recruiting members and of creating shared grounds of interest and commonality among them. For the Harry Potter Alliance, for example, a shared love for the content world of Harry Potter enables participants of diverse backgrounds, ages, and views, to come together for political action such as protecting marriage equality and other actions we are now learning of.

This review of some of the literature in political science assists us to base our claims within an ongoing scholarly conversation. The argument we make and the cases we examine place our research team in a key position in this conversation, not only implementing the up-to-date arguments in the field, but taking them several steps further. Still, we must also keep in mind that the dominant view of many is that politics only matters when it is performed within the frame of political parties. The argument that other forms of politics matter too will need to be justified in response to such claims.

References

Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, see http://www.civicyouth.org/

Colby, A. (2008). The place of political learning in college. Association of American colleges and universities, Spring / summer, 4-12.

Dalton, R.J. (2008). The good citizen: How a younger generation is reshaping American politics. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA (2009). The American Freshman: National norms for 2008. Los Angeles, CA. Available: http://www.heri.ucla.edu/publications-brp.php

Longo, N. (2004). The new student politics: Listening to the political voice of students. The Journal of Public Affairs 7(1), 1-14.

Shea, D.M., & Green, J.C. (2007). The turned-off generation: Fact and fiction. In D.M. Shea and J.C. Green (Eds.), Fountain of youth: Strategies and tactics for mobilizing America’s young voters (pp. 1-18). Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

[1] Thanks to Ben for raising this point, as well as challenging it.

[2] Colby (2008), who is also worried that the increase in civic engagement does not lead to political learning, but still thrives to accept wider forms of participation, sees as a key criterion of distinction that “political activities are driven by systemic-level goals, a desire to affect the shared values, practices, and policies that shape collective life” (p. 4).

Explain yourself: Bridigng Discourse and its applications to Participatory-Civic Engagement Groups

When individuals engage in behavior that might be considered inauthentic by other group members, they, or other members, often engage in bridging discourse to explain why the behavior is congruent with the idea of being period; in doing so, they demonstrate that their behavior is linked to the same ideology to which other group members link their behavior. When group members engage in behavior that others see as incongruent with the group’s ideology, they risk portraying themselves as deviant and indicating that they believe the ideology of the group is unimportant. Other group members may feel that such actions reflect poorly on the group as a whole, and this may change the collective identity of the group. When individuals engage in bridging discourse, they protect themselves, or others, from stigma but also maintain the collective identity of the group. Members accomplish this by reinterpreting the group’s ideology, redefining their behavior, or offering explanations as to why they should be excused from meeting the group’s standards.

Decker (2010)

Stephanie Decker’s recent article in the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography argues for the idea of bridging discourse, that is, discourse that individual members of a group may employ in order to explain inconsistencies of action with the overall group identity, in an attempt to maintain cohesion. While the ethnographic research that serves as the basis of the paper is focused on participants in the SCA (Society for Creative Anachronism), this model of intragroup discourse may prove useful for the group, especially in discussing groups that have a upper management which may be attempting to change the group’s focus/direction.

Decker’s piece as well as the work she draws on is primarily based on Goffman’s frame analysis work. Decker’s work builds from Snow et. al (1986) work on frame bridging. While frame bridging refers to the connections between two or more different, but compatible organizations with each other or an organization with an individual who has a different, but compatible frame, bridging discourse deals with intragroup discussion between individual members or between a member and the group in whole. Decker also cites research on frame alignment by Oliver and Johnson (2000), which focused on recruiting practices in social movement groups. Here Decker is trying to expand the types of groups this sort of research can focus on, but it is worth noting that, given the research group’s focus on social groups that are also, in various ways, social movement groups, that this line of work bears further inquiry.

Briefly, bridging discourse is described by Becker as a set of strategies employed by group members to help ease incongruities between their actions and the group’s overall identity in order to smooth over those differences and maintain group cohesion. In her work with the SCA, she describes several instances of members employing bridging discourse to explain their actions. In particular, the main use of bridging discourse in the SCA was explaining why someone was not in period dress. Sneakers and rubber soled boots in particular served as a focus for group dissonance since one of the group’s overall tenet is to maintain the illusion of period (medieval and early renaissance) garb. Examples of bridging discourse used was claiming to be a new member and therefore ignorant of group policy, apologizing profusely and claiming a time/logistical snafu prevented the proper garb from being worn, or (in cases where members are in period, but culturally clashing garb) by incorporating the seeming inconsistency into an elaborate backstory for the persona one was portraying in SCA events. Members who are reacting to this discourse may make exceptions to the behavior, especially if the deviant member in question is considered a valued member of the group, in order to maintain group identity.

Of course, this bridging discourse has certain limits. Members can choose not to employing bridging discourse and accept a reputation as a deviant within the group. Secondly in particular, if enough members behave consistently outside of the group’s frame, it may shift the frame of the group so that members are no longer deviating from the group. Decker notes that “[group members] explained that, while they did not want to include members who did not make an attempt to be historically authentic, they found it important for the sake of the group to accommodate members with various interpretations of the ideology… while such members often noted that this flexibility alters the concept of authenticity and lowers the groups standards for historically accurate behavior… this flexibility ultimately made it possible for the group to survive,” (292).

Bridging discourse, then, might be something worth noting in our conversations and other research on the group we are looking at. Especially considering groups such as Racebending and the HPA, which have or are planning to change the scope of the group’s identity from a top down angle, it may be useful to see how individual members react to this shift and whether bridging discourse is utilized to either enforce the old group identity or the new one. In a group such as IC, it may be useful to see if bridging discourse is utilized among members when talking about events or the group identity in itself.

Reference

Decker, S. (2010). Being Period: An Examination of Bridging Discourse in a Historical Reenactment Group. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 39(3) 273-296.

Icy Dead People

The sound is both unmistakable and unforgettable. Equal parts siren call, banshee cry, and woeful lament, the anguished scream of the female horror victim is a primal sound that instantly evokes unsolicited dread from somewhere deep within.

This image, often accompanied by an overhand stabbing pantomime reminiscent of Psycho, is the typical response that greets me whenever I mention my research interests in Horror. Many of my peers speak to me about their brushes with the genre and how various movies or television shows have served to instill a perpetual sense of fear in them: to this day, friends will trace a hatred of clowns back to It, apprehension about blind dates to Audition, and a wariness of European hostels from, well, Hostel. Those around me see Horror as the representation of a force that serves to limit action, crafting a clear binary that contrasts the safe and acceptable with the foreign and dangerous.

To be sure, there is a certain amount of truth to what my friends believe; to live in a post-9/11 world is to be familiar with fear. As an American, I have been engaged in a “War on Terror” for my entire adult life, warned that illicit drugs fuel cartels, and have heard that everything under (and including) the sun will give me cancer. Sociologists like Barry Glassner talk about how our attempts to curb our fears just make us more afraid and Eve Ensler chimes in with a discussion of how an obsession with security only serves to instill an even greater sense of insecurity. Fear has become a sort of modern lingua franca, allowing people to discuss things ranging from economic recession, to depression, to moral politics. Perhaps worse yet, I have developed in an educational system that fostered anxiety as I struggled to get the best grades and test scores, desperate to find meaning in my college acceptances and hoping for validation in achievement—growing up, there were so many ways to fail and only one way to succeed. Whole parts of my identity have been defined by my fears instead of my hopes and although I rebel against the notion of being controlled by this emotion, I realize that it continues to have a pervasive effect on my life and my actions. I continue to quell the fears that I will not live up to expectations, that I will grow lonely, and that I will one day forget what I am worth.

And I don’t think I’m alone.

[Read more…]

[Read more…]

Star Wars and Political Discussion

I’ve recently started the process to join a guild for Star Wars: The Old Republic and have begun to wonder about how the fictional universe’s basic structure lends itself to fans developing ideas regarding political participation. Beyond the simple binary of the Republic/Empire, I am interested to see how fans talk about political values and ideals. While much of this discussion has already taken place around published media, I am interested to see how the introduction of an MMO during the Old Republic period will allow discourse that differs from Star Wars Galaxies. I think it will be interesting to see how the forums develop over the next 10 months as the game leads up to launch. In that vein, here are some of the things that I’ve been thinking about lately.

Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, and Participatory Fandom

Teaching Old Brands New Tricks

http://www.cato.org/pub_display.php?pub_id=4192

I’ve also including some of the readings that I used for a recent paper on Invisible Children.

Alice James and the Spectacle of Sympathy

Examining Social Resistance and Online-Offline Relationships

Muscular Christianity and the Spectacle of Conversion