Zombies are, for me at least, a rich subgenre of horror that allows us to explore a host of issues that deal with issues of politics, economics, and class. Even scholars who are only vaguely familiar with the topic can often cite the cultural critiques latent within George Romero’s Dead trilogy.

Over the past two years, our group has bandied about different concepts that deal with pop culture and the political, with mention of terms like “movements,” “groups,” and “masses” calling to mind the ways in which issues of power and powerlessness manifest in the zombie genre. Although we can talk about the larger ways in which horror intersects with notions of power, zombies, out of all the monstrosities, provide a more direct understanding of the relationship between individuals/communities and minorities/majorities.

In particular, I am curious about the ways in which zombies are being reinterpreted in modern culture: employed in the 1930s as symbols of colonialism, resurrected in the 1960s to showcase the ills of consumer culture, and tweaked in the 2000s to evidence fears surrounding biological agents, zombies have always been, in some ways, representative of a fear of being subsumed by the masses. And yet the rise in zombie subculture seems to have split in recent years: although we continue to preoccupy ourselves with surviving the impending zombie apocalypse (hint: take up parkour), we also seemingly exhibit an increased desire to become zombies through events like zombie walks/crawls. Moreover, looking to online spaces—which are, in their own ways, very much about communities—we also glimpse a thriving group of individuals who choose to play as zombies in various forms.

What does all of this mean for the ways that we consider ourselves in relation to the communities around us?

Although groups like Invisible Children seem quite distinctly different from zombies, I wonder about how individuals in both organizations negotiate their identity as members of a highly-visible subculture that, most likely represents a national minority, might at times be a majority in local societal contexts. Moreover, in both situations, we have (primarily) young people who toe the line between belonging to a group and maintaining a sense of individuality within the mass—or maybe members do not fear being “swallowed up” by the group at all.

The more that I learn about how zombie culture is being enacted and embodied in real world practices, the more that I think about how lessons for political action can be extracted and utilized. But then again, zombies have always been about politics.

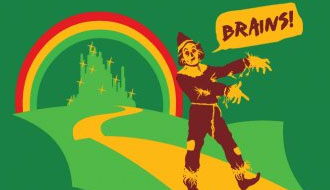

Chris Tokuhama studies popular culture, youth, Suburban/Gothic Horror, and media as a graduate student in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California while balancing a full-time job in the Office of College Admission. Primarily interested in modern mythologies and narrative structures, Chris has often reimagined the Scarecrow as a zombie. Comments, questions, and Starbucks gift cards can be sent to tokuhama [at] usc [dot] edu.