The sound is both unmistakable and unforgettable. Equal parts siren call, banshee cry, and woeful lament, the anguished scream of the female horror victim is a primal sound that instantly evokes unsolicited dread from somewhere deep within.

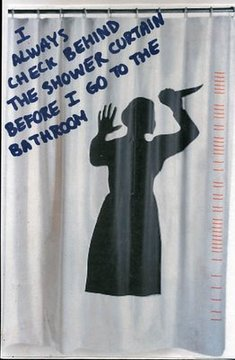

This image, often accompanied by an overhand stabbing pantomime reminiscent of Psycho, is the typical response that greets me whenever I mention my research interests in Horror. Many of my peers speak to me about their brushes with the genre and how various movies or television shows have served to instill a perpetual sense of fear in them: to this day, friends will trace a hatred of clowns back to It, apprehension about blind dates to Audition, and a wariness of European hostels from, well, Hostel. Those around me see Horror as the representation of a force that serves to limit action, crafting a clear binary that contrasts the safe and acceptable with the foreign and dangerous.

To be sure, there is a certain amount of truth to what my friends believe; to live in a post-9/11 world is to be familiar with fear. As an American, I have been engaged in a “War on Terror” for my entire adult life, warned that illicit drugs fuel cartels, and have heard that everything under (and including) the sun will give me cancer. Sociologists like Barry Glassner talk about how our attempts to curb our fears just make us more afraid and Eve Ensler chimes in with a discussion of how an obsession with security only serves to instill an even greater sense of insecurity. Fear has become a sort of modern lingua franca, allowing people to discuss things ranging from economic recession, to depression, to moral politics. Perhaps worse yet, I have developed in an educational system that fostered anxiety as I struggled to get the best grades and test scores, desperate to find meaning in my college acceptances and hoping for validation in achievement—growing up, there were so many ways to fail and only one way to succeed. Whole parts of my identity have been defined by my fears instead of my hopes and although I rebel against the notion of being controlled by this emotion, I realize that it continues to have a pervasive effect on my life and my actions. I continue to quell the fears that I will not live up to expectations, that I will grow lonely, and that I will one day forget what I am worth.

And I don’t think I’m alone.

For me, Horror touches on our desire to explore these sorts of fears along with other states of liminality, pushing the boundaries as we attempt to expand the extent of the known. We find fascination in Gothic figures of vampires and zombies for they represent a transgression of the norm and find exhilaration in Horror’s potent blend of sex and violence as a means of experiencing violations of the cultural standard without suffering the real life repercussions. Underneath the morality pleas of many horror films (with their constant insistence that “Good girls don’t!”) lies a valid method of exploration for audiences. Even scenes of torture, which most definitely assume a different meaning in a post-9/11 world, can be understood as a method of exploring what humanity is like at its extremes; both assailant and victim are at limits (albeit very different ones) of the human condition and Horror provides us with a voyeuristic window that allows us to vicariously experience these scenes.

Television, in particular, holds a special place in my heart as a representation of shared cultural space and for its successive engagements with its audience. Not being an active churchgoer, I find that television is my religion—I set aside time every week and pay rapt attention, in turn receiving moral messages that reflect my vision of the world but also challenge it. Perhaps more than that, good television has the ability to assume varied meanings for its audiences, either providing multiple narratives (and thus entry points) or lending itself to a reworking by viewers whose productions then become a part of a larger cultural context. Through television, I learn that “my story” is really “our story”—or, more accurately, “my stories” overlap with “our stories.”

Lately, my story has been one that contemplates death and immortality. Fascinated by instances of the dead coming back to life, I found myself drawn to Pushing Daisies, intending to revisit the series with a more critical eye.

Although I generally found Pushing Daisies mildly amusing, I realized that I failed to connect to the show because death seemed to fundamentally lack consequences. I accepted this surrealistic world where people can come back to life at the touch of a finger but was dismayed to realize that the experience of death was likened to a momentary pause—the show even compared the process to the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty—a move, that to me, signaled a relative lack of respect on a show that was, in part, predicated upon death. Ignoring the biological reasons why revival would not necessarily produce the results desired by amateur private investigator and pie maker Ned, I fought against the show because I wanted (and expected) the program to touch on some of the core issues surrounding individuals’ relationship to death. Perhaps overly critical of the series, I compared what I saw onscreen to Six Feet Under, Buffy’s resurrection during season six, and Torchwood; I expected the dead to find their reawakening much more jarring then what I witnessed. I caught glimpses of discussions about the afterlife and the terror of dying but these moments were subsumed by the relatively straightforward convention of detective procedural. I was mad at the show because it didn’t give me the opportunity to explore feelings in this area and therefore did not help me prepare for the eventuality of my own demise. Conversely, the shows that I had loved, and responded to, contained elements of Horror that enabled me to work through my own death, ironically making the final act less frightening.

I thought back to my college years and my initial exposure to a film that has become one of my favorites: Battle Royale. In stark contrast to the American horror films that I had seen, the Japanese style assaulted my psyche instead of my body (the gore was, in fact, somewhat laughable considering my previous exposure to violent media). The basic premise of the movie is that a class of randomly selected junior high school students is sent to an island and given three days to fight for their lives. At the end of the contest, only one student can survive—otherwise everybody dies. Despite an admittedly bleak and distressing exterior, the movie does a remarkable job of demonstrating different survival strategies as part of a metaphor for success in the Japanese school system. I found myself watching the movie over and over again as I contemplated what my own path would be if I were placed in a similar situation. Would I take the opportunity to seek revenge against those who had wronged me? Would I use seduction to kill? Would I enter into a tenuous agreement with my friends to reenact a cooperative society despite our paranoia? Would I try to fight against the system and seek a way out?

Pondering this issue caused me to ruminate on what a life is worth. More specifically, what was my life worth?

Although mildly obsessed with the issue of worth thanks to my early exposure to The Joy Luck Club, I had never really thought about what I would do to stay alive until I watched Battle Royale and later, in my senior year of college, another movie that would change the course of my life.

Curled up on a couch with takeout Chinese food and some wine, I watched as my date slid Saw out of its red Netflix pouch and into the DVD player. The opening scenes of the movie flashed before me as I speared some steamed vegetables with my chopsticks.

My plate clinked gently as I placed it on the coffee table.

(This was, I soon realized, a very poor choice for a date movie.) Although my head spun, in a rush of emotions I found myself recalling the same thoughts that I was forced to confront while watching Battle Royale: What gave my life meaning? What would I do to survive?

My stomach shrank as I felt something inside of me break. While the gore was not exceptionally appealing (the fear of suffering before dying was firmly placed in my mind after an ill-advised viewing of Misery in my younger days), the sinking feeling that I experienced came from the realization that I would be a target of the Jigsaw killer for I didn’t appreciate my life. Long after the movie had finished, I was terrified that I would be abducted by someone in a pig mask and end up in a basement chained to a wall. “After all,” I thought to myself, “Didn’t I deserve what was coming to me? Just a little bit?”

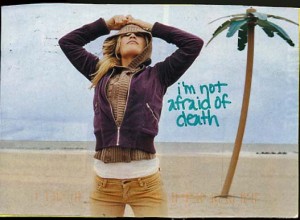

After a week of sleepless nights, I finally realized that the solution to my problem was actually rather simple: start living my life in a way that was meaningful and fulfilling. It was at that point (particularly poignant for someone who was about to graduate from college) that I challenged myself to start taking risks and to do things that scared me.

My personal history with the genre is part of the reason that I am incredibly optimistic for generations that have grown up surrounded by images of Horror. In contrast to the conventional notions, with its frozen faces and cowering victims, I see the field as an incredible space to explore some of the concepts that most challenge society. While it may be true that storytellers working in the genre of Horror aspire to scare us, they do so as a means to a larger goal: fright is used as a provocation that forces us to consider why we are terrified in the first place. Whether we realize it or not, exposure to Horror allows us to understand the mechanisms of fear and, in the process, realize that the unknown is becoming the known. In my mind, Horror possesses a wonderful coping aspect; although not necessarily therapeutic, I believe that areas like American Gothic can be empowering. When we choose to experience a work of Horror, we make a concession that the content could (and probably will) frighten us—an acquiescence that gives the material the freedom to explore fringe or minority issues.

It is in these groups—some of the traditionally oppressed—that I see Horror’s greatest potential, but it is in youth that I place my greatest hopes.

So while some of my current work with this research group is focused on the ability of popular culture to propel individuals’ energies outward as they become activists, engaged citizens, or public participants, I cling steadfastly to my roots as I wonder how Horror can turn the gaze inward in order to grapple with the darkness within. I am fully aware that this process of self-discovery is quite scary (who knows what you might find?) but I find myself eternally hopeful that fans of horror will learn to brave the dark places of themselves, secure in the knowledge that friends and family will always be there to draw them back. I am hopeful that, through Horror, people will come to understand who they are and accept themselves for that. I am hopeful that individuals will learn to step outside of themselves in order to offer their help to others who might also be suffering.

Ultimately, I am also hopeful because I have learned that young people are incredibly resilient and innovative—like the brunette heroines of 80’s slasher films—they can accomplish some amazing things if given half a chance.

Chris Tokuhama studies popular culture, youth, Horror, and media as a graduate student in the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California while balancing a full-time job in the Office of College Admission. Primarily interested in mythical origins and narrative structures, Chris is unashamed to admit that he will only watch Asian horror films during the day. Comments, questions, and Starbucks gift cards can be sent to tokuhama [at] usc [dot] edu.

This is kind of brilliant Chris — what a valuable tangent! I have always wondered about and wanted to pay more attention to individuals’ personal histories as drivers for civic participation. It might appear that many young people — while not obviously “politically” involved, as some folk in poli sci might allege (see Neta’s entry) — simply want to feel a part of something greater than themselves or relate to other young people because family life is often not fulfilling, and that’s why they think or say aloud that they are members of say, IC or HPA; your suggestion is that unconsciously or subconsciously, a large number of young people might be actually working through their own fears — of death, of being victims of apathy, of being apathetic, of becoming Dementor-like in order to fight illusory-or-not Dementors. The idea that our childhood fears and ‘grave’ desires never leave us, and that we sometimes wrought them into meaningful civic activity, is provocative, to say the least. It definitely is a ponderable reason as to why we do so many things we do. Basically, if it isn’t some positive spirituality that propels us down deep, then what negative else does?; is pertinent because those who do not channel their fears into making their lives meaningful by participating civically or doing something else ‘positive’, what happens to them — who are they, if not our real-life vampires and zombies?

Also, how would we ever be able to research people’s subconscious reasons? It would take a very personal interview indeed. Maybe if group members close to each other interviewed each other and share their data, we’d know the deeper personal reasons why people actively try to fill their lives with meaning.

Anyway, thanks for sharing your personal story!

This is kind of brilliant Chris — what a valuable tangent! I have always wondered about and wanted to pay more attention to individuals’ personal histories as drivers for civic participation. It might appear that many young people — while not obviously “politically” involved, as some folk in poli sci might allege (see Neta’s entry) — simply want to feel a part of something greater than themselves or relate to other young people because family life is often not fulfilling, and that’s why they think or say aloud that they are members of say, IC or HPA; your suggestion is that unconsciously or subconsciously, a large number of young people might be actually working through their own fears — of death, of being victims of apathy, of being apathetic, of becoming Dementor-like in order to fight illusory-or-not Dementors. The idea that our childhood fears and ‘grave’ desires never leave us, and that we sometimes wrought them into meaningful civic activity, is provocative, to say the least. It definitely is a ponderable reason as to why we do so many things we do. Basically, if it isn’t some positive spirituality that propels us down deep, then what negative else does?; is pertinent because those who do not channel their fears into making their lives meaningful by participating civically or doing something else ‘positive’, what happens to them — who are they, if not our real-life vampires and zombies?

Also, how would we ever be able to research people’s subconscious reasons? It would take a very personal interview indeed. Maybe if group members close to each other interviewed each other and share their data, we’d know the deeper personal reasons why people actively try to fill their lives with meaning.

Anyway, thanks for sharing your personal story!