What symbols matter for an inauguration? There was no crown for Obama. But for mortals with a smartphone it was possible to get a  badge, if you were one of the 20+ million users of FourSquare. To receive the badge for inauguration weekend, users had to “check in” with their smartphone at the National Mall on inauguration day, or at an official service event location around the country.

badge, if you were one of the 20+ million users of FourSquare. To receive the badge for inauguration weekend, users had to “check in” with their smartphone at the National Mall on inauguration day, or at an official service event location around the country.

A commercial gimmick? Not entirely. It was an official partnership between the Presidential Inaugural Committee (PIC) and FourSquare, announced just days before the National Day of Service. The new badge (see right) is the first for volunteerism from FourSquare, a company with “check-in” functionality that is valued at $600 million.

is the first for volunteerism from FourSquare, a company with “check-in” functionality that is valued at $600 million.

But for Obama’s inauguration, is this the right symbol? The new badge comes atop a year of intense debate about the value of “gamification” and digital badges. Incentives are tricky for civic life, especially with what I’ve called direct action games. Are inaugurations different?

Spectacle is a central question for the inauguration and the new badge. In his inauguration address, Obama vilified spectacle declaring that “we cannot… substitute spectacle for politics.” Yet the same President switched the event date to maximize the potential for media and to be memorable. Is spectacle necessarily bad?

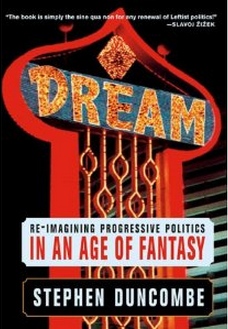

The curious possibility is that America needs more ethical spectacle. The term comes from NYU media theorist Stephen Duncombe, whose book has shown that politics is inherently tied to spectacle. But that doesn’t make it bad. In fact, good and ethical spectacle is necessary for democracy, and necessary for the political imagination.

shown that politics is inherently tied to spectacle. But that doesn’t make it bad. In fact, good and ethical spectacle is necessary for democracy, and necessary for the political imagination.

What’s different with ethical spectacle is that it invites ordinary participants to contribute and change the spectacle; moreover, ethical spectacle does not hide the truth. (Duncombe has a more detailed criteria in his book for the curious.)

What kind of contribution is invited by Obama’s spectacle? Beginning after the 2008 election, Obama started a new tradition with the inauguration to include a “Day of Service” with ties to MLK Day and volunteerism. This year Obama again invited Americans to contribute their time. On the service day, he explained to press that:

“This inauguration [is] a symbol of how our democracy works and how we peacefully transfer power, but it should also be an affirmation that we’re all in this together, and we’ve got to look out for each other, and we’ve got to work hard on behalf of each other.”

On the positive side, the Day of Service gives people a way to contribute, beyond listening passively to a speech on television. The danger embodied in the FourSquare badge is that volunteers become stage props in a bullet-proof event, a spectacle without real agency to modify the symbolism or reflect on its truth.

The need for ethical spectacle, according to Duncombe, is to expand and drive our political imagination. Rational thought and duty must include difficult compromises. But we still need political dreams to drive the national debate, to spur engagement, and these dreams must celebrate ideals that are always beyond what is immediately possible. Obama understands the need for dreams in his rhetoric, including the inauguration address.

The ethics dilemma is about participation. The Obama administration was solely in charge of the ceremony, from the raising of the right hand, to the choice of who is positioned in the background for the TV cameras. Volunteering locally on a prior day is admittedly a way to contribute, and it can be personally meaningful. But service is typically subordinate, and rarely prioritizes debate or pushes volunteers toward greater agency.

Similarly, digital platforms like FourSquare can make the spectacle more participatory and open to change, or they can divert attention back to the paths that others have prescribed. Badges can challenge us to try something new and to share our accomplishments. But they also risk setting up templates that are too narrow, and hiding opportunities.

Sadly, FourSquare is already obfuscating its democratic potential for 20+ million users. Under their activity model, if you visit a location (like a physical bookstore) more times than anyone else over several weeks, then you become its “mayor.” (For example, I was once the mayor of the Stories Bookstore in Echo Park.) But the mayor title just gives consumer discounts, not any powers of speech. Their empty use of the term is an insult to all mayors who got the job for the greater good, rather than a free lunch. Yes, open deliberation might intimidate the FourSquare investors, but that’s exactly my point: there is a tyranny of the possible.

Where should badges start? Why not look back to November 6th. On election day I received a simple “I voted” sticker for my shirt. The sticker was not my incentive for voting, but it had an effect: for the rest of the day, that sticker spurred conversation with strangers, business owners and roommates. The sticker let me bring my private act of voting into the public sphere, to take a public role on my own terms. It was a badge that supported ethical spectacle.

Can we democratize the badge? In fact, we must. The badges are coming, whether through FourSquare or elsewhere. Our choice is how to make them meaningful, especially when tied to government. Along with our democracy, the standards for what makes a “good citizen” are evolving. There was no crown for Obama, but this year there was a badge for good service. The badge counted some actions, but not others. Before the next inauguration, it is worth debating which badges are worthy of our democratic imagination, and to whom they are accountable.