Yesterday, thousands of sites participated in an online protest to raise awareness about two pieces of anti-piracy legislation making their way through Congress. The bills in question, best known as SOPA and PIPA, are often said to “break the internet.” The phrase appears frequently in both academic and journalistic contexts and is used about as often by supporters of the legislation as opponents.

And, yet, in spite of the proliferation of the phrase, critics struggle to describe how a “broken” internet will look, feel, or function differently from the (presumably unbroken) internet their readers use everyday. Sure, you can spend a few hours browsing through countless youtube videos, earnest comment threads, detailed expert analyses, and even a flowchart – but what would this regulation feel like?

Blocking access to all of Wikipedia’s English-language articles was a powerful awareness-raising tactic but it more closely resembled the Department of Homeland Security’s habit of seizing domains than the enforcement techniques described in SOPA or PIPA. Unlike the digital crime scene tape employed by the DHS, enforcement in SOPA and PIPA follows what Tarleton Gillespie calls “a strategy of forced invisibility.” Today, a link appears in Google searches; tomorrow, it doesn’t.

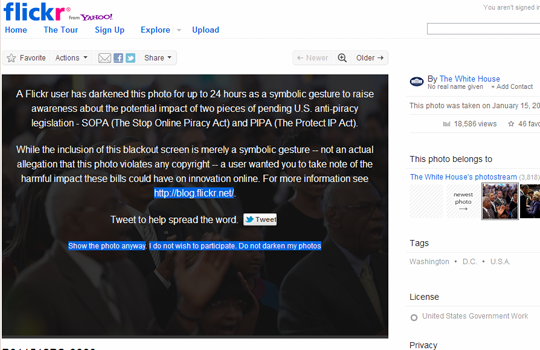

Flickr approached the day of protest differently from its peers. Rather than blackout its logo (like Google) or its content (like Reddit), Flickr built new functionality into its software that enabled users to censor each other:

“Flickr is letting members darken their photos — or the photos of others — for a 24-hour period to deprive the web of the rich content that makes it thrive. Your symbolic act will help draw attention to this issue and let others know about the potential harmful impacts of these bills.” — Zack Sheppard, Flickr blog, January 18, 2012

By mid-afternoon, Flickr users had darkened over 200,000 photos, including (for a limited time) all of the photos on The White House stream.

Flickr’s participatory tactic shifted the affective timbre of the protest from anger at a denial of access to uncertainty at a loss of control. Whereas the blacked-out Wikipedia asked a simple – perhaps hyperbolic – question, “What if the U.S. government blocked this site?”, Flickr forced users to critically consider their expectations regarding the stewardship of photos they upload.

Positioned as both censor and censored, users collectively acted out a possible enforcement scenario. As the day wore on and unwitting users encountered their darkened photos, hundreds took to a thread on the help forum to express their support, frustration, glee, anger, and utter confusion during the protest.

“I fully support the cause, just not the means by which I am being force to get involved[.] Choosing to black out my photos is a decision for me to make, not for Flickr to allow others to do so without my consent[.] I understand and accept a server error that disables my photos. But not an deliberate act like this.” — Jericho777, January 18, 2012

For the thousands of users who found their photos darkened, Flickr’s protest software provided an opportunity to experience “what censorship really feels like” – but the specific mechanics of the protest still fell short of simulating the “strategy of forced invisibility” inscribed in the proposed legislation. Under a regime governed by these laws, Flickr photos accused of copyright infringement would not appear darkened – they simply would not appear at all.

YouTube’s Content ID system provides an all-too-real example of internet regulation enacted in running code (with disastrous consequences for free speech.) Flickr’s software-assisted protest of SOPA/PIPA suggests that simulation might provide a powerful tactic for engaging with proposed media regulation in the future. By producing software that simulates the effect of a given piece of legislation, critics can move past vague hyperbole (“SOPA will break the internet”) to demonstrate how it will actually feel to use the internet under the proposed regulatory regime.

(Cross-posted to Hacktivision.)