(See also the series overview for this Hotspot on civic crowdfunding.)

Lana Swartz

In 2013, indie studio Lab Zero Games launched an IndieGoGo campaign to crowdfund the expansion of their game Skullgirls. It was highly successful, raising $829,049, well over its stated goal of $150,000.

But then there was a problem.

Zero Lab CEO Peter Batholow wrote on a gaming messageboard:

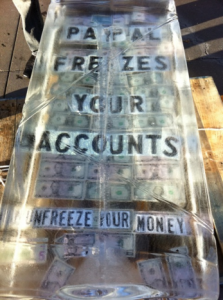

“Whee! Paypal’s freeze on our account is making it so that I can’t pay people today.”

Apparently, PayPal was concerned that funders would ask for their money back if they weren’t happy with the way the expansion turned out.

Batholow said:

“They are effectively treating it as a loan. I mean, the guy flat out said: ‘Until the threat of chargebacks has passed, PayPal is effectively financing your development.’”

When a PayPal representative asked him if Lab Zero would be able offer refunds if supporters demanded their money back en masse, he said:

“I said no, because, well … we’re not. […] The whole point of crowdfunding is to give us the money to develop stuff — not to take out a loan.”

After outrage in the indie game community and coverage on tech blogs, PayPal lifted restrictions on the Lab Zero account, agreeing to instead keep $35,000 in “collateral.”

Lab Zero games is hardly the first to be burned by PayPal’s policies. Indeed, there are thousands of posts from those whose accounts have frozen on gripe sites like PayPalSucks.com, Screw-PayPal.com, PayPalWarning.com.

One blogger pointed out that ordinary people often fared worse than those with some degree of online fame:

“If you ever find yourself under the thumb of a corporate monolith [like PayPal], make sure you have an army of Internet followers to back you up.”

One forum poster, commenting on the Lab Zero Games case, suggested:

“Sounds like someone needs to indiegogo/kickstarter an alternative to PayPal.”

Perhaps. In fact, KickStarter does not even use PayPal. A post on its company blog explains that after projects have been successfully funded, no refunds to backers are allowed and that Amazon Payments is the only payment intermediary able or willing to support this process.

But using Amazon Payments also has its own infrastructural restrictions. Because Amazon Payments does not support non-U.S. recipients, all KickStarter project creators had to hold a U.S. bank account. More recently, KickStarter has begun supporting U.K.-based creators, processing these payment themselves directly. By using PayPal, IndieGoGo is able to compete with KickStarter on its geographic reach, calling itself “The World’s Funding Platform.”

But alternative payment systems are rapidly proliferating, and most are hoping to make their reputation in the wake of frustration with PayPal. This has implications for “civic” crowdfunding as well.

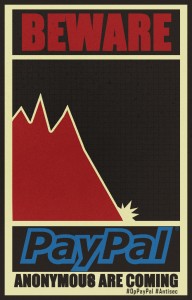

One such rival, WePay, received attention when it became, according the Washington Post, the “de facto official” way to donate money to Occupy. WePay became popular among Occupy supporters in large part because PayPal had, in violation of its own terms of service, participated in an embargo of Wikileaks.

As a Wired blogger noted, there was an “element of theater” to Wikileaks’ struggles against censorship by its data and domain-name service providers because the information was mirrored elsewhere, including on more secure servers, but that the attack on WikiLeaks’ money flow was, in contrast, “the real deal.”

Indeed, according to Wikileaks, the embargo “blocked over 95% of our donations, costing tens of millions of dollars in lost revenue.”

<< back to the series overview for this Hotspot on civic crowdfunding